Introduction Railways feel familiar: you tap a card, wait on a platform, and glide through tunnels or across open country. Yet behind that everyday routine is a web of engineering choices and historical decisions that shape how trains run, how safe they are, and why systems differ from one city or nation to the next. If you enjoy testing your transit knowledge, it helps to know what makes rail networks tick, from track geometry to power supplies and the rules that keep trains separated.

Signals, switches, and the art of spacing trains A rail line is more than two steel rails. One of the most important ideas is separation: ensuring trains do not occupy the same stretch of track at the same time. Traditional railways use block signaling, dividing the line into segments. If a block is occupied, the signal behind it warns or stops the next train. Modern metros may use communications based train control, which can allow shorter gaps by continuously tracking train position and speed.

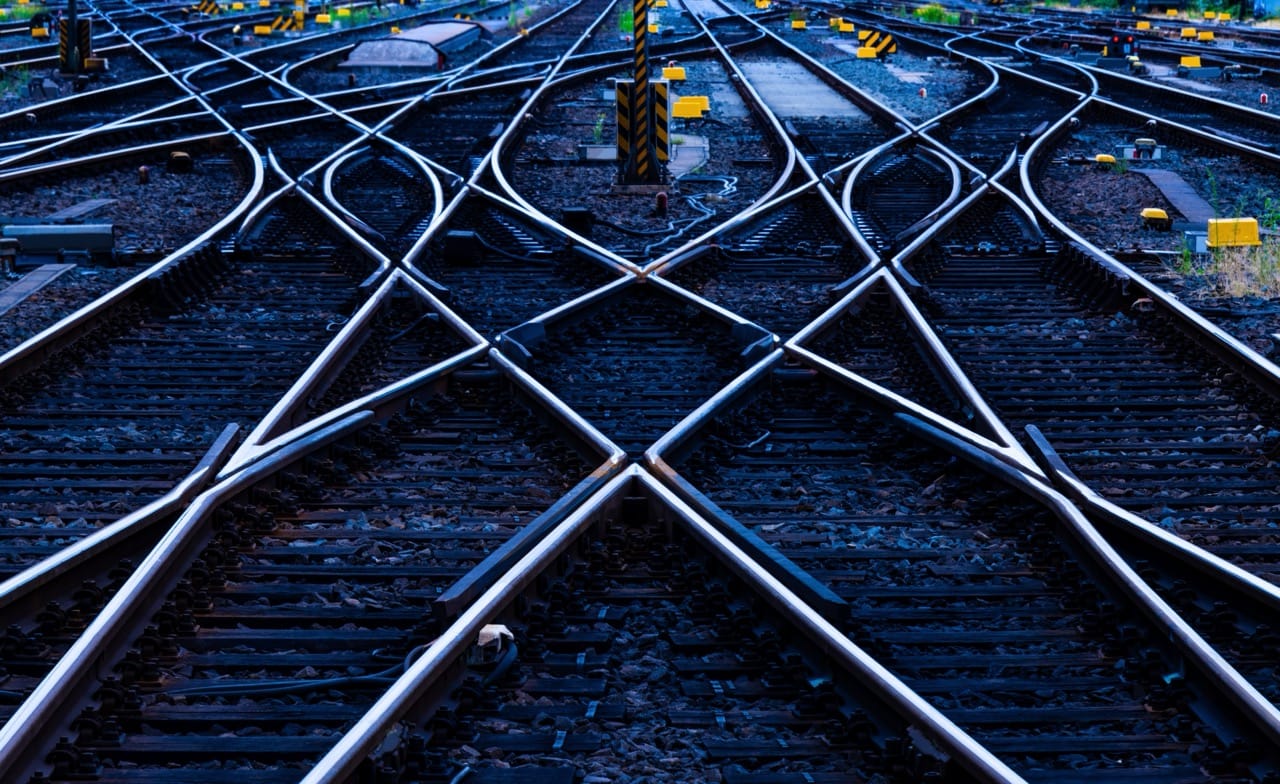

Switches, also called points or turnouts, are another key element. They guide wheels from one track to another using movable rails. High speed turnouts are long and gently curved, while yard switches can be tighter because trains move slowly. Switch heaters in cold climates prevent snow and ice from locking them, a small detail that can decide whether a rush hour runs smoothly.

Gauges, wheels, and why trains stay on the rails Track gauge is the distance between the rails. Much of the world uses standard gauge, but broad and narrow gauges also exist due to historical choices, geography, and cost. Gauge affects vehicle design, stability, and interoperability. When networks meet at different gauges, freight may be transferred, bogies swapped, or special variable gauge systems used.

Steel wheels on steel rails have surprisingly low rolling resistance, which makes trains energy efficient for moving large loads. They stay guided by the wheel profile: a slightly conical tread helps the wheelset self center on straight track and negotiate curves, while flanges provide a safeguard. Curves are often banked with superelevation so passengers feel less sideways force, and speed limits reflect how tight a curve is.

Power systems: third rail, overhead wire, and diesel Urban metros commonly use either third rail or overhead catenary. Third rail keeps equipment compact but requires careful insulation and protection because of exposed high voltage. Overhead electrification is common for main lines and high speed rail, supporting higher power and speed. Different regions use different voltages and frequencies, which is why some trains are built as multi system units that can cross borders without stopping.

Diesel traction remains useful on routes without electrification. Many modern trains are diesel electric: the engine drives a generator, and electric motors turn the wheels. Hybrid and battery trains are increasingly used for short non electrified sections, reducing noise and emissions in stations and tunnels.

Stations, platforms, and the choreography of dwell time A train schedule depends heavily on dwell time, the minutes spent at stations. Platform design, door width, passenger flow, and accessibility features all matter. Level boarding reduces boarding time and improves mobility for everyone. Some busy systems use platform screen doors to improve safety and climate control, and to reduce delays caused by track intrusions.

Safety rules and the human factor Rail safety is built on redundancy. Automatic train protection can enforce speed limits and stop trains that pass a signal at danger. Procedures for dispatchers, drivers, and maintenance crews are standardized because small errors can have large consequences. Even the simple rule of keeping a clear line of sight in yards, or using horn signals at crossings, is part of a layered safety culture.

Conclusion From the outside, rail travel looks straightforward, but every trip depends on a network of design decisions: how trains are spaced, how tracks connect, what power is delivered, and how stations handle crowds. The next time you ride, notice the signals, listen for the change in motor sound, or look for the subtle banking on curves. Those details are the difference between a system that merely moves and one that moves millions reliably, on time, and safely.