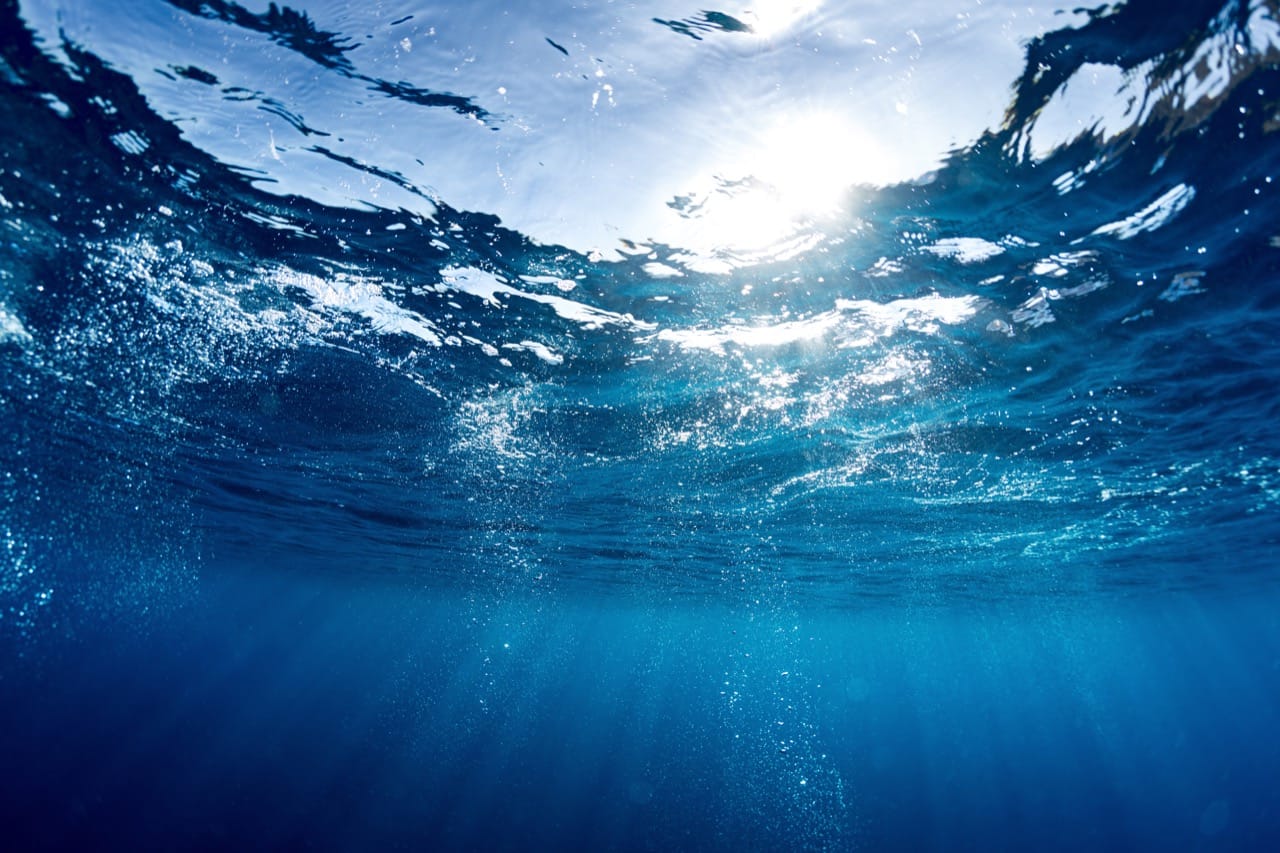

Introduction The ocean covers most of Earth, yet much of it remains less familiar than the Moon. Beneath the surface is a realm ruled by pressure, chemistry, darkness, and ingenious biology. From bright coral reefs to trenches deeper than mountains are tall, ocean life and ocean physics are tightly linked. Understanding the deep sea means following energy, water movement, and the clever adaptations that let organisms survive where humans cannot.

Sunlight, zones, and the basic problem of food Near the surface, sunlight powers photosynthesis, feeding plankton that support food webs reaching up to tuna, seabirds, and whales. But light fades quickly. By about 200 meters, the ocean enters the twilight zone, where vision still matters but colors vanish and sunlight is weak. Below that lies the midnight zone, where darkness dominates and food becomes scarce. Many deep animals depend on marine snow, a slow rain of dead plankton, fecal pellets, and other organic scraps drifting down from above. Because this food supply is unreliable, deep sea creatures often conserve energy with slow metabolisms, soft bodies, and patient hunting strategies.

Pressure, temperature, and life at the extremes Pressure increases by about one atmosphere every 10 meters. At trench depths, it can exceed 1,000 atmospheres, enough to crush unprotected equipment. Deep sea animals cope with flexible tissues, pressure tolerant proteins, and membranes tuned to stay functional in cold, high pressure water. Temperature is usually near freezing in the deep, but hydrothermal vents break that rule. At mid ocean ridges, seawater circulates through hot rock, emerges loaded with chemicals, and can reach temperatures above 300 degrees Celsius before mixing with cold seawater. Life there does not rely on sunlight. Instead, microbes use chemosynthesis, turning chemicals like hydrogen sulfide into energy. Tube worms, clams, and other animals often host these microbes, forming ecosystems that can boom in an otherwise food poor world.

Bioluminescence and the deep sea light show In darkness, many organisms make their own light. Bioluminescence is produced by chemical reactions involving molecules such as luciferin and enzymes like luciferase, sometimes aided by symbiotic bacteria. Deep sea light serves many purposes: attracting mates, luring prey, confusing predators, or creating camouflage. A fish may glow on its belly to match faint light from above, making it harder for predators below to see its silhouette. Others flash suddenly to startle attackers or release glowing particles as a decoy.

Senses beyond human experience Where vision is limited, other senses shine. Many fish detect subtle vibrations and water movement with the lateral line system. Sharks and rays can sense tiny electric fields produced by muscle contractions in prey, helping them hunt even when buried in sand or hidden in murky water. Some species also use smell over long distances, following chemical trails in currents. Sound travels efficiently underwater, so whales and other animals use vocalizations to communicate across vast ranges.

Currents, gases, and the ocean as a climate engine Ocean circulation moves heat around the planet. Surface currents driven by winds redistribute warm and cold water, shaping regional climates. Deeper circulation, often called the global conveyor belt, forms when cold, salty water sinks in polar regions and slowly travels through ocean basins. This movement also affects how gases dissolve in seawater. Cold water holds more dissolved gas, including oxygen and carbon dioxide. As water masses sink, they can carry oxygen to depth, supporting deep ecosystems. At the same time, the ocean absorbs a large share of human produced carbon dioxide, which alters seawater chemistry and can make it harder for corals and shell forming organisms to build their structures.

Conclusion The blue frontier is not a uniform abyss but a layered, dynamic system where physics and biology constantly interact. Pressure shapes bodies, chemistry fuels vent communities, and currents connect distant regions into one global machine. The more we learn, the more the deep sea reveals itself as both strange and essential, a hidden world that influences climate, supports remarkable life, and still holds countless secrets waiting beneath the waves.