Introduction Look up on a clear night and you are seeing a mix of nearby neighbors and unimaginably distant objects, all telling parts of the universe’s story. Astronomy can feel huge and abstract, but many of its most interesting mysteries connect to simple questions: Why does one planet have a longer day than another, what makes a star different from a planet, and why do some worlds shine even though they do not produce light? Exploring these ideas turns stargazing into a kind of detective game, where every point of light has a clue behind it.

Planets, nicknames, and what they really mean Several planets have popular nicknames that hint at their appearance or history. Mars is called the Red Planet because iron-rich minerals in its soil and dust oxidize, giving it a rusty color. Venus is sometimes called Earth’s twin because it is similar in size, but its thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and crushing pressure make it wildly un-Earthlike. Saturn is famous for its rings, but those rings are not solid bands. They are made of countless pieces of ice and rock, ranging from dust grains to house-sized chunks, all orbiting in a thin, broad disk.

Days, years, and the strange clocks of other worlds A day is one rotation of a planet, while a year is one orbit around the Sun. Those two cycles vary dramatically across the solar system. Mercury rotates slowly, so one Mercury day is longer than its year in a particular sense: it takes about 59 Earth days to rotate once, but only about 88 Earth days to orbit the Sun. Venus is even more extreme, rotating very slowly and in the opposite direction of most planets. That backward spin is called retrograde rotation, and it means the Sun would appear to rise in the west and set in the east if you could stand on Venus’s surface.

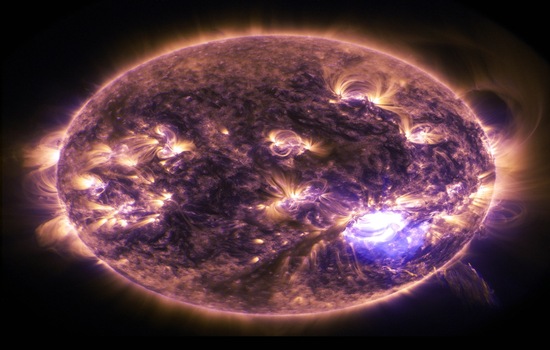

Stars, reflected light, and why moons glow Stars shine because they generate energy through nuclear fusion in their cores, converting hydrogen into helium and releasing enormous amounts of light and heat. Planets and moons do not fuse atoms, so they do not make their own visible light. Instead, they reflect sunlight. The Moon looks bright because it is close, not because it is especially reflective. In fact, its surface is darker than many people expect, more like weathered asphalt. The phases of the Moon are a geometry lesson: you are seeing different portions of its sunlit half as it orbits Earth.

Icy moons and hidden oceans Some of the most exciting places for discovery are not planets at all, but moons. Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus are covered in ice, yet evidence suggests warm, salty oceans beneath their surfaces. On Enceladus, geysers of water vapor and ice particles spray from cracks near its south pole, feeding Saturn’s E ring. These hidden oceans matter because liquid water, energy, and chemistry are key ingredients for life as we know it, making these moons prime targets in the search for habitable environments.

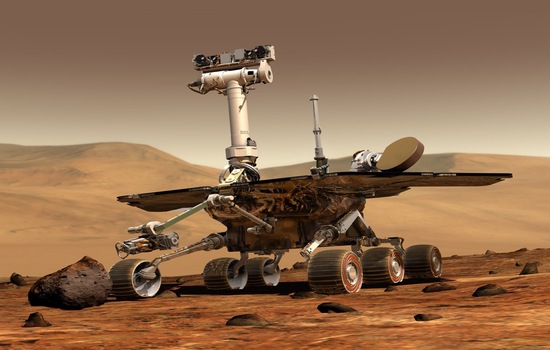

Tools we send beyond Earth Space exploration depends on clever instruments. Telescopes in space avoid atmospheric blur and can observe wavelengths blocked from the ground. Probes and rovers act as robotic field scientists, analyzing rocks, measuring radiation, and sniffing atmospheres for chemical clues. Even gravity becomes a tool: spacecraft often use gravity assists, stealing a tiny bit of a planet’s orbital energy to change speed and direction, allowing missions to reach distant targets with less fuel.

Conclusion The universe rewards curiosity with layers of surprising detail. A planet’s nickname can point to chemistry, a long day can reveal a strange spin history, and an icy moon can hide an ocean that reshapes how we think about life’s possibilities. The next time you take a quiz or glance at the stars, remember that each answer connects to a real, ongoing investigation. Astronomy is not just about memorizing names. It is about learning how to ask better questions of the sky.