Introduction Reality feels familiar because our brains are built to make quick predictions. But nature does not always follow our everyday intuition. The rules that govern motion, light, heat, and the tiniest particles were uncovered through careful experiments, and they often reveal a world that is stranger and more interesting than common sense suggests. This article previews the kinds of ideas behind Reality’s Rulebook Riddles, offering conversation-ready facts and a few classic surprises.

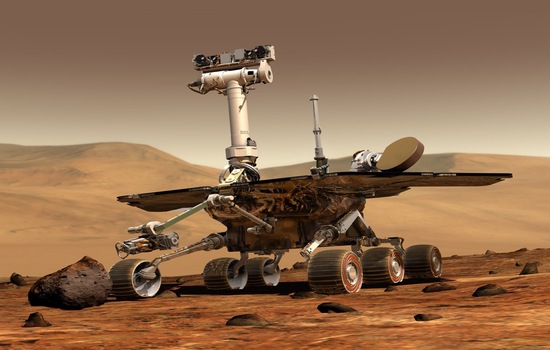

Motion and forces: why “obvious” can be wrong One of the biggest intuition traps is believing that motion needs a continuous push. In daily life, objects slow down unless you keep applying force, so it feels like force causes motion. What experiments showed is that force causes changes in motion, meaning acceleration. If friction and air resistance vanished, a sliding puck would keep moving at constant speed in a straight line without any additional push. This is why spacecraft can coast for long periods: there is little resistance in space.

Another counterintuitive idea is that heavier objects do not fall faster in the same conditions. Galileo’s famous demonstrations captured the point, and modern tests in vacuum chambers confirm it dramatically: a feather and a hammer hit the ground together when air is removed. In the real world, air resistance makes the feather drift, which is why the vacuum condition matters so much.

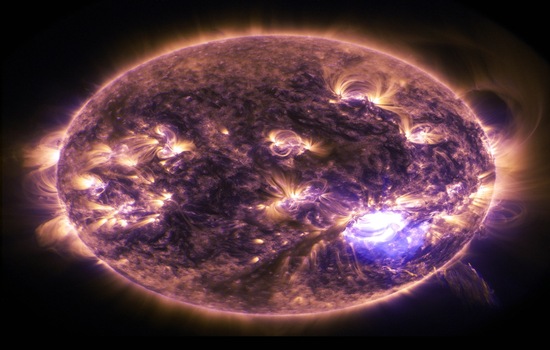

Energy and heat: the hidden direction of time Energy is conserved, but it changes form. A rolling ball’s motion can become heat through friction, and that heat spreads into the environment. This helps explain why some processes seem to have a preferred direction. You can easily warm your hands by rubbing them, but you cannot rub warm hands together and reliably make a ball roll faster. The energy is still there, but it becomes more dispersed and less useful for doing organized work.

A classic everyday example is the cooling of hot coffee. It always approaches room temperature, not the other way around, because heat flows spontaneously from hotter to cooler regions. Scientists describe this with the idea of increasing disorder, but you can also think of it as energy spreading out.

Light and perception: what you see is not always what is there Light behaves like a wave in many situations, producing interference patterns where brightness depends on tiny differences in path length. The famous double-slit experiment shows that even a single beam of light can create a striped pattern of bright and dark bands, as if light is combining with itself.

Your eyes add another layer of surprise. Color is not a property stored inside objects; it is a result of how surfaces reflect certain wavelengths and how your brain interprets the mix. That is why the same shirt can look different under sunlight and indoor bulbs. It is also why optical illusions can be so convincing: your visual system is making its best guess based on context.

The very small: rules that challenge common sense At tiny scales, the rules become even less intuitive. Particles such as electrons do not behave like miniature billiard balls with definite paths. Instead, experiments suggest they are described by probabilities until measured. This is not just philosophy; it changes what can be built and measured. For example, some properties cannot be pinned down precisely at the same time, which limits how sharply we can define certain pairs of quantities.

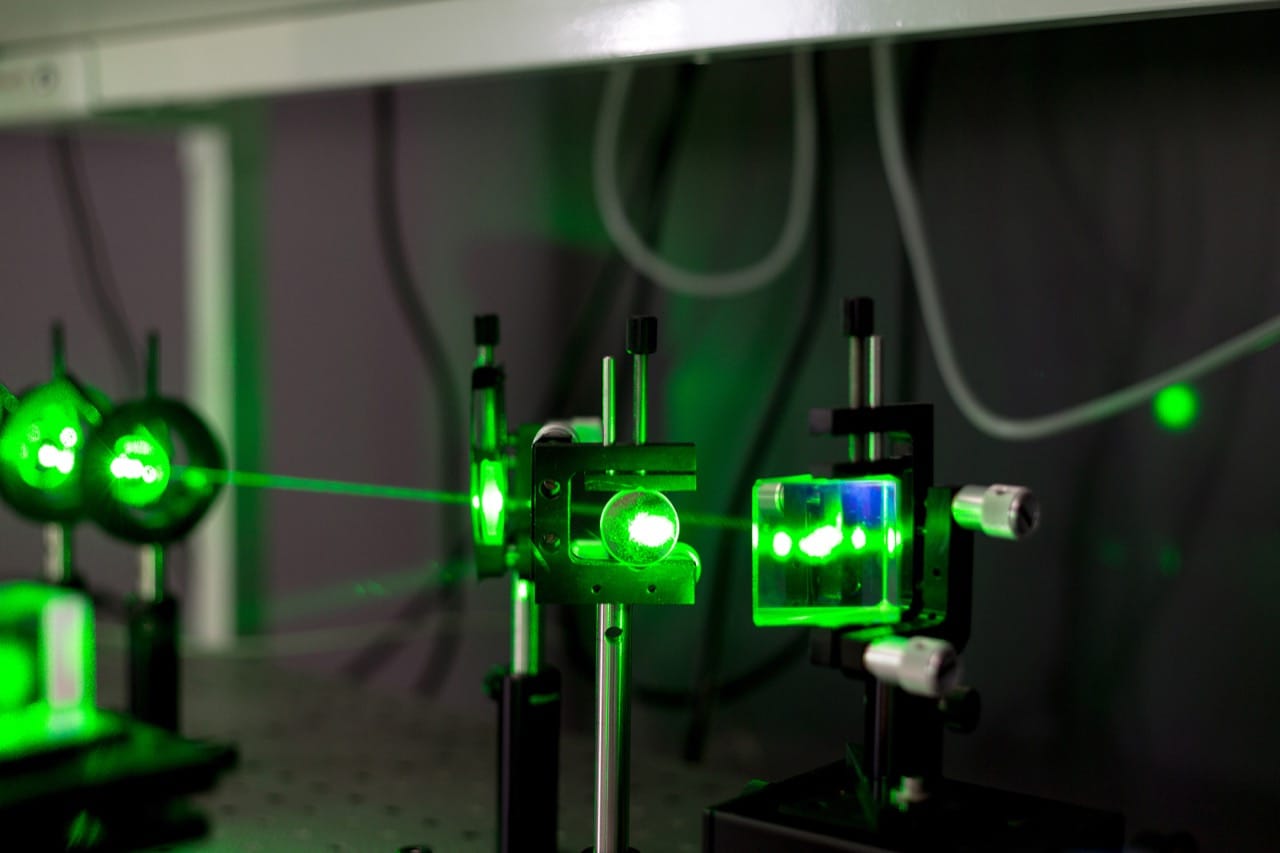

Yet the small-scale world is not just weird, it is useful. Technologies like lasers, LEDs, and computer chips rely on quantum behavior. Even magnetic resonance imaging in hospitals depends on subtle quantum properties of atoms.

Conclusion Reality’s rulebook is full of surprises because nature is not obligated to match our instincts. The best riddles in science come from small changes in conditions, like removing air resistance or isolating friction, that reveal the underlying rules. As you take on questions about motion, energy, light, and the microscopic world, look for the hidden assumptions. The reward is not just a higher score, but a sharper sense of how scientists learned what is true and a collection of facts that make the everyday world feel newly fascinating.