Introduction Rocks are easy to overlook because they seem still and silent. Yet every pebble, cliff, and sidewalk slab carries a record of Earth’s past and a hint of its future. Geology is like reading a long mystery novel written in minerals, pressure, heat, and time. By noticing textures, colors, and shapes, you can uncover stories of ancient oceans, rising mountains, drifting continents, and the recycling of crust deep inside the planet.

Minerals: the planet’s ID cards Minerals are the basic ingredients of rocks, and each mineral has a specific chemical recipe and crystal structure. That structure controls many familiar properties. Hardness explains why quartz-rich sand is common on beaches: quartz resists scratching and survives long journeys. Cleavage describes how a mineral breaks along flat planes, like mica splitting into thin sheets. Color can help, but it can also mislead because impurities change it. A better clue is streak, the color of a mineral’s powder, which stays more consistent. Even tiny crystals can act like fingerprints, letting geologists identify where a rock formed and what conditions shaped it.

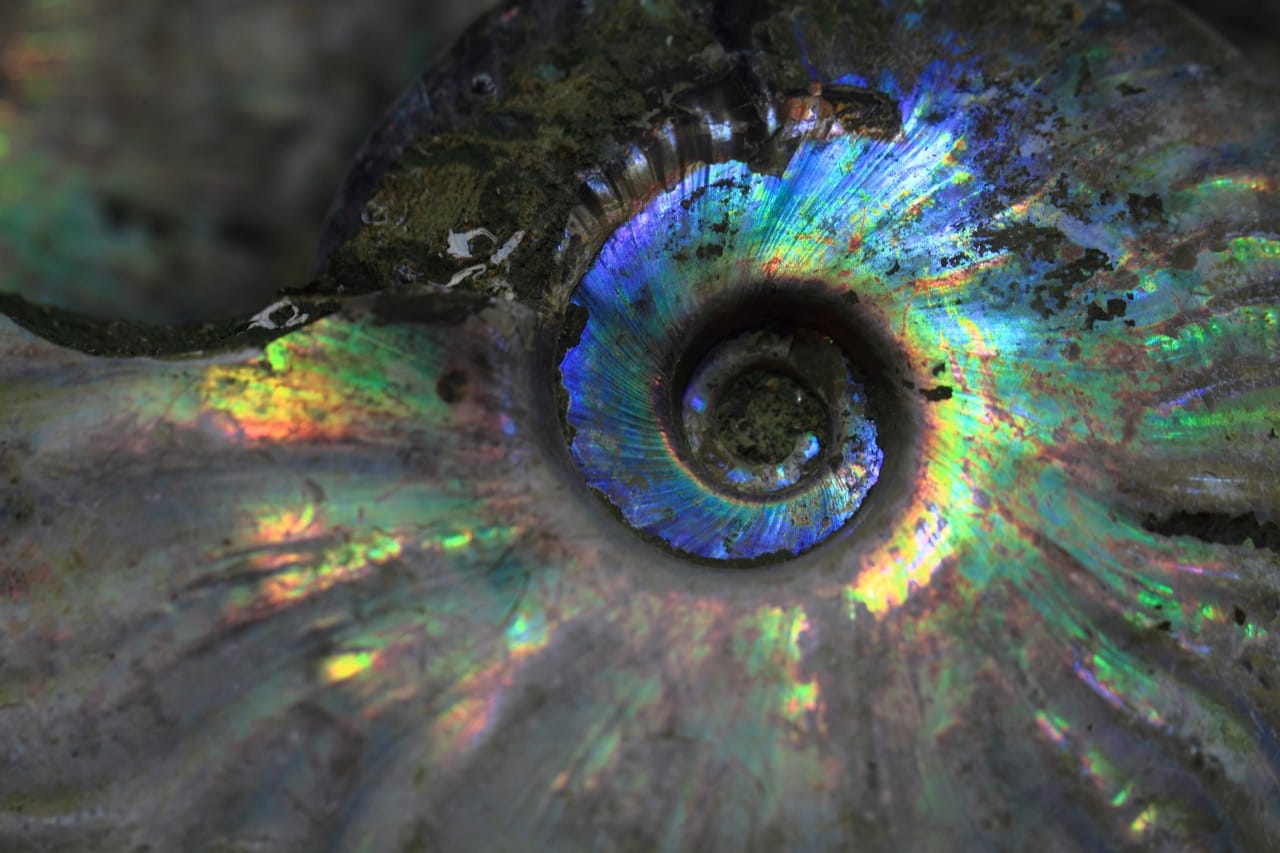

How rocks form: three pathways, countless stories Igneous rocks form when melted rock cools and solidifies. Slow cooling underground gives crystals time to grow large, producing coarse-grained rocks like granite. Fast cooling at the surface makes fine-grained rocks like basalt, common in volcanic regions and oceanic crust. Sedimentary rocks form from particles, shells, or chemical precipitates that accumulate in layers. They often preserve fossils and ripple marks, capturing snapshots of old environments such as river deltas or shallow seas. Metamorphic rocks form when existing rocks are changed by heat, pressure, and fluids without fully melting. This can create new minerals and textures, such as the banding in gneiss or the shiny alignment of minerals in schist.

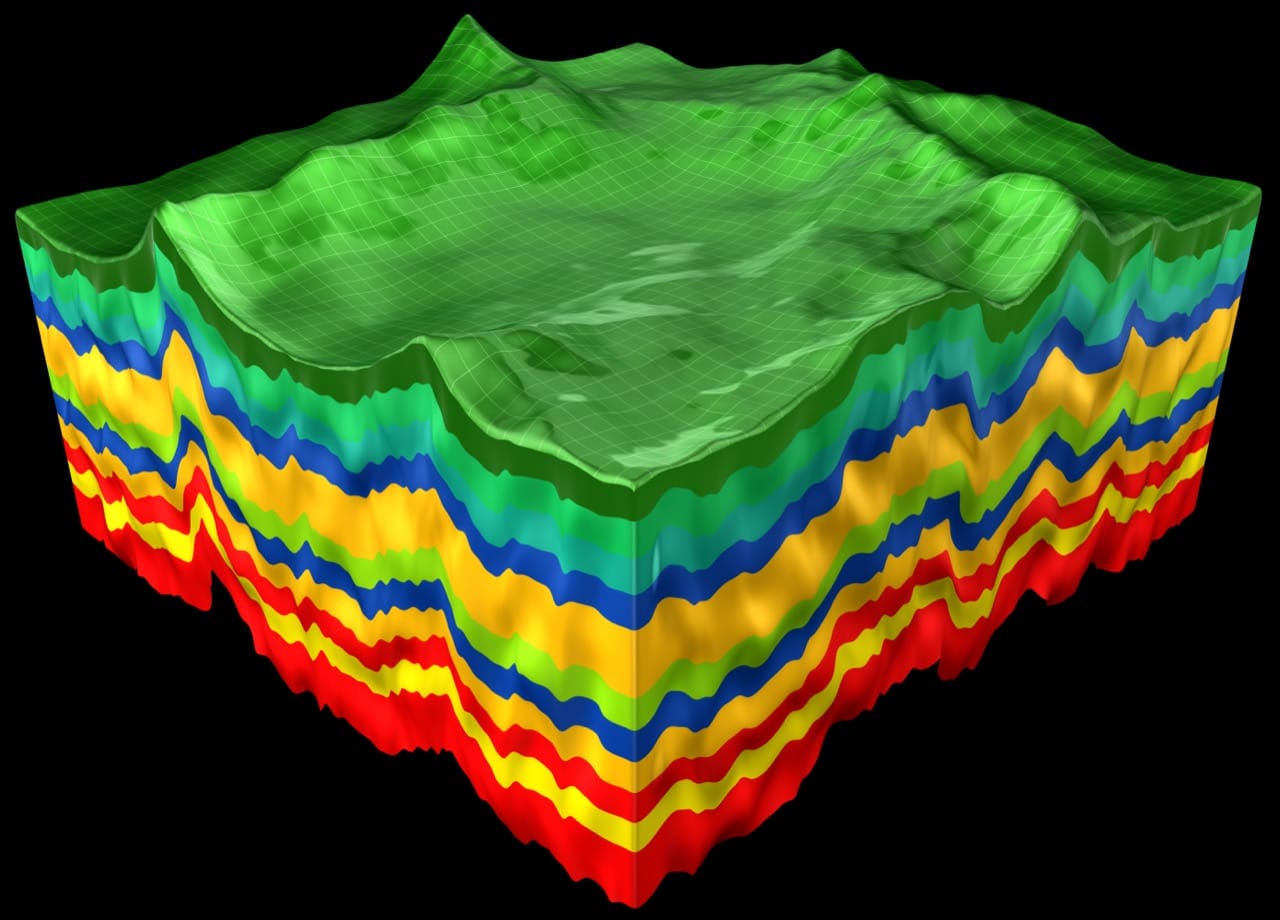

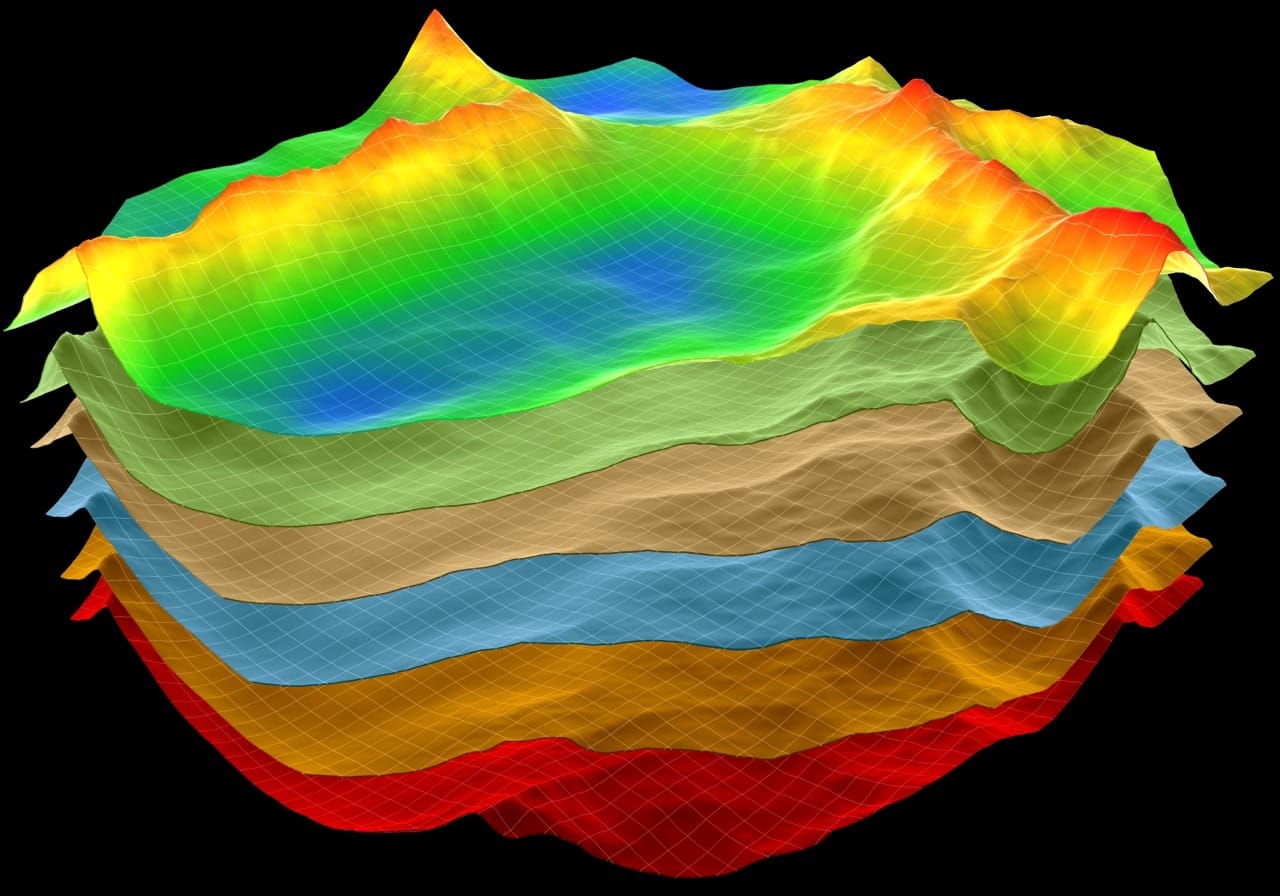

Deep time and the rock cycle Earth constantly reuses its materials. Mountains erode into sediment, sediment becomes rock, rock is buried and transformed, and some of it melts to start again. This rock cycle is powered by plate tectonics and by gravity pulling material downhill. Because many processes are slow, geologists rely on clues to measure deep time. Relative dating uses principles like superposition, where younger layers usually sit on older ones. Absolute dating uses radioactive elements that decay at known rates, turning certain minerals into natural clocks. Together, these tools reveal a planet that is about 4.5 billion years old.

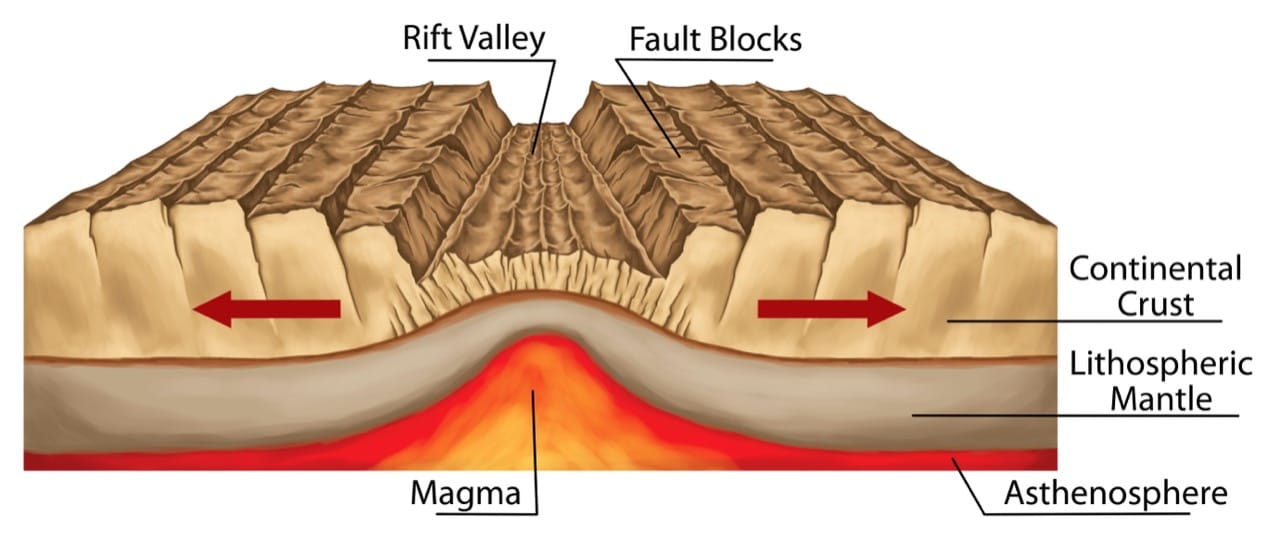

Moving plates, building landscapes The continents fit like puzzle pieces because they were once joined. Plate tectonics explains that Earth’s outer shell is broken into moving plates that collide, separate, and slide past each other. Where plates converge, crust can crumple into mountain ranges or sink into the mantle at subduction zones, fueling volcanoes. Where plates diverge, new crust forms at mid-ocean ridges. Transform boundaries, where plates grind sideways, can produce powerful earthquakes. These motions also influence coastlines, ocean basins, and the distribution of resources such as ore deposits and geothermal energy.

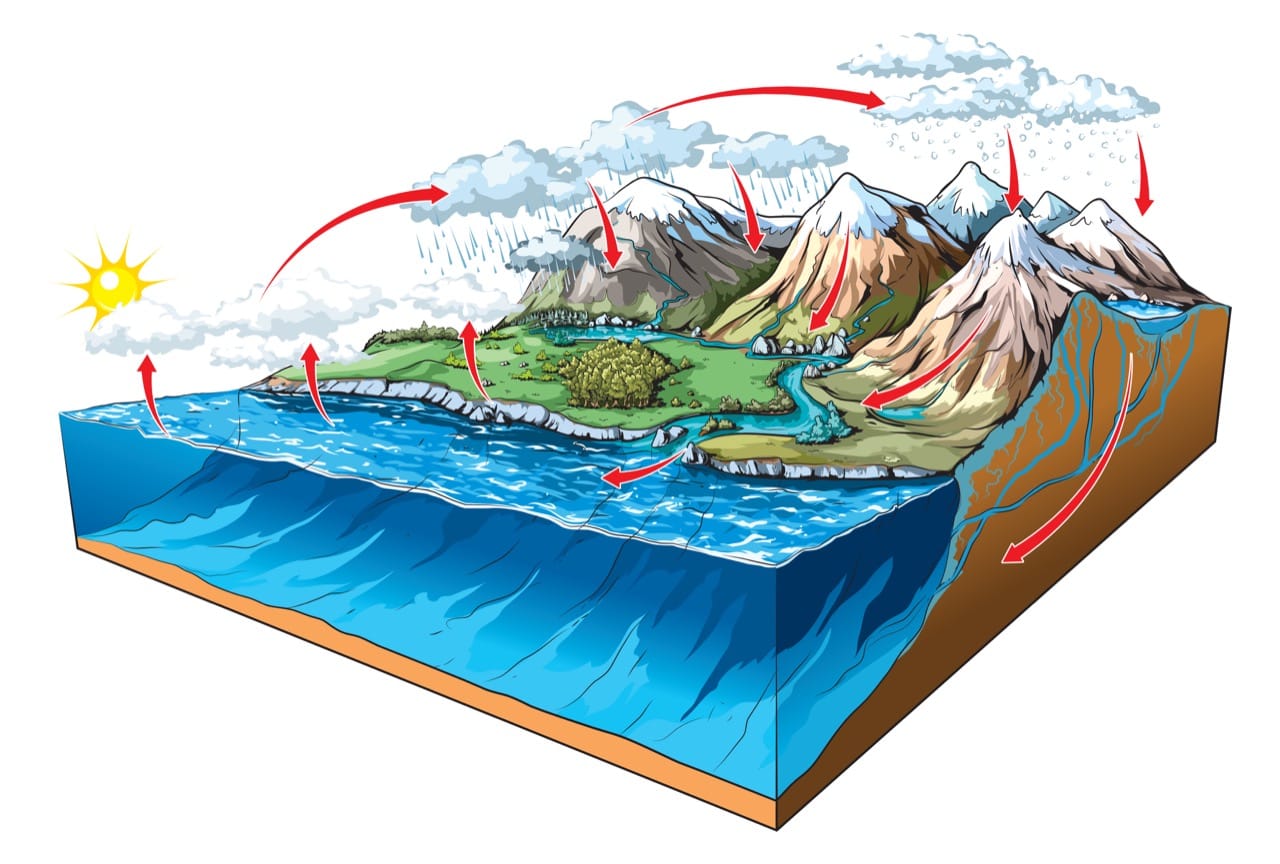

Ice, water, and wind: the surface sculptors Even without dramatic plate collisions, landscapes change relentlessly. Rivers carve valleys and sort sediment by size, leaving gravel in fast water and mud in quiet basins. Glaciers act like slow bulldozers, grinding bedrock into fine flour and leaving U-shaped valleys and scattered boulders far from their source. Wind shapes dunes and can transport dust across continents. Over time, these everyday processes create the sand you step on, the soil that grows food, and the cliffs that frame coastlines.

Hazards with geological roots Earth’s energy can be dangerous. Earthquakes release built-up stress along faults, while volcanoes erupt when gases and magma rise toward the surface. Landslides often follow heavy rain or shaking, especially on steep slopes with weak layers. Understanding rock types and structures helps predict where hazards are more likely and how communities can reduce risk.

Conclusion The ground beneath you is not a static backdrop but a dynamic system with a long memory. Minerals record chemistry, rocks preserve environments, and landscapes reveal the forces that shaped them. By learning to read these clues, you begin to see Earth’s hidden blueprint: a planet that builds, breaks, and rebuilds itself across immense spans of time, leaving evidence in the smallest grain of sand and the tallest mountain ridge.