Introduction In the mid twentieth century, a new wave of artists began treating the modern world itself as their subject. Instead of distant myths or solemn historical scenes, they looked to supermarket shelves, movie stars, comic strips, and political headlines. Their art was loud, bright, and instantly legible, often borrowing the visual language of advertising. What emerged is widely known as Pop Art, a movement that turned mass culture into high-impact visual statements and challenged what museums and galleries were supposed to value.

From consumer goods to cultural icons Pop Art grew in a world saturated with mass media. Television expanded rapidly, magazines and billboards multiplied, and product packaging became more sophisticated. Artists responded by using familiar objects and faces as raw material. Andy Warhol became famous for repeating images of Campbell soup cans and Marilyn Monroe, showing how fame and consumer desire could be manufactured and endlessly reproduced. Roy Lichtenstein drew from comic books, enlarging dramatic panels into monumental paintings that made a single moment feel both heroic and slightly absurd. Claes Oldenburg pushed everyday objects into playful extremes, building oversized sculptures of things like hamburgers and household items to explore how consumer culture shapes our sense of scale and importance.

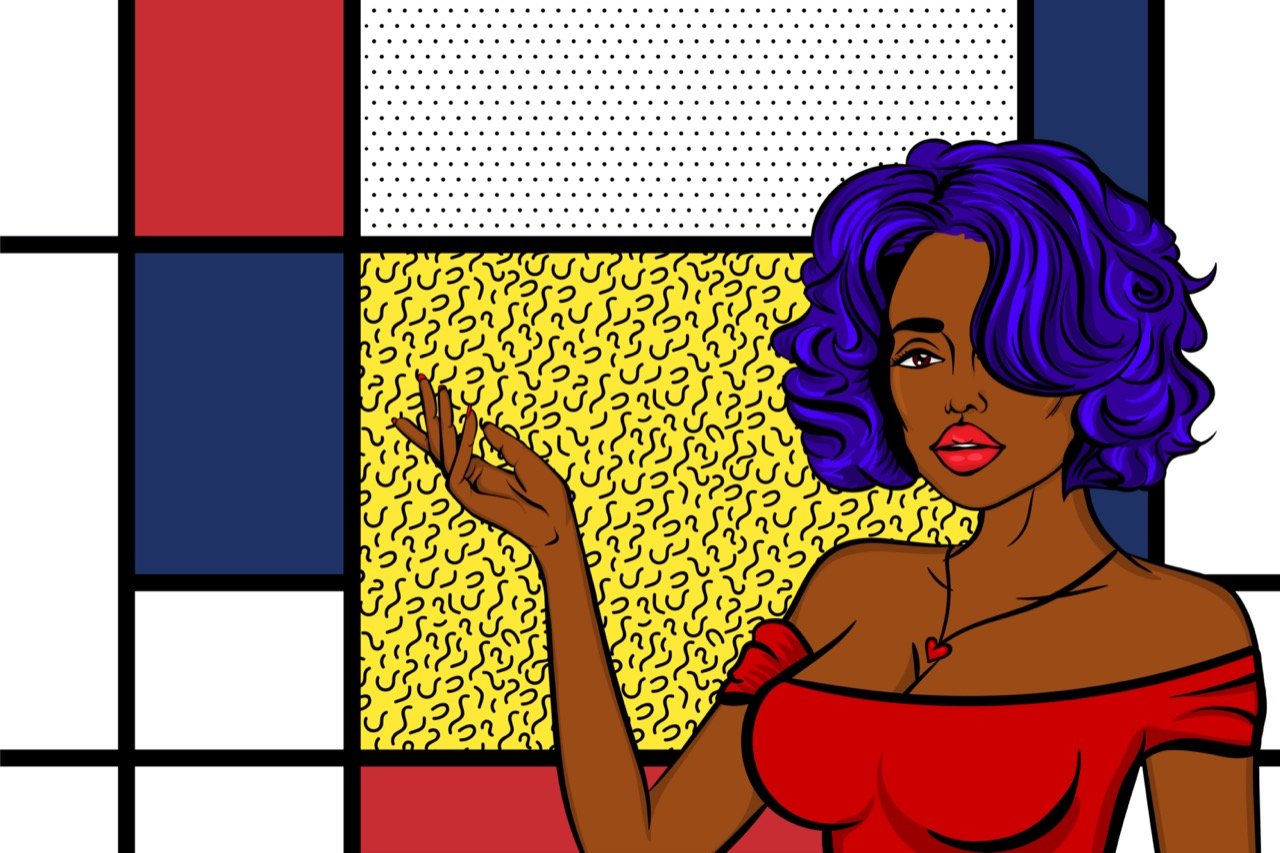

Techniques that looked like the modern world The look of Pop Art was not accidental. Many artists adopted methods that echoed commercial printing. Screenprinting, strongly associated with Warhol, allowed images to be transferred through a mesh screen and repeated with variations in color and alignment. The process embraced small imperfections, which could make a celebrity portrait feel both glamorous and strangely mechanical. Lichtenstein became closely linked to benday dots, a printing technique used in comics and newspapers to create shading and color through tiny dots. By hand painting these dots at a large scale, he transformed a cheap reproduction method into a signature style, inviting viewers to notice how images are constructed.

Humor, irony, and repetition as commentary Pop Art often feels fun at first glance, but it frequently carries sharp observations. Repetition is a key device. When you see the same face or product again and again, it can start to feel less like a treasured icon and more like a commodity. This was part of the point: Pop artists explored how modern life turns people, politics, and even tragedy into consumable images. The tone can be ironic, but it is not always purely critical. Some artists were fascinated by the energy and accessibility of popular imagery, and their work can feel like both celebration and warning.

Headline exhibitions and lasting influence Pop Art gained momentum through major exhibitions and the growing attention of critics and collectors. Its rise also reflected broader social shifts, including postwar prosperity, youth culture, and the expanding power of advertising. Over time, Pop Art helped open the door for later movements that engaged with media, identity, and appropriation. Today, its influence is visible everywhere from graphic design and street art to music branding and social media aesthetics.

Conclusion Pop Art remains instantly recognizable because it speaks the visual language of everyday life. By transforming comics, consumer goods, and famous faces into art, Pop artists asked a lasting question: what does a culture choose to worship, and how do images shape that choice? The bright colors and bold outlines may feel playful, but behind them is a serious curiosity about modern desire, mass communication, and the strange power of repetition.